Existing drug found to dampen chemo side effects in breast cancer — in a dish

Patients with HER2-positive breast cancer face something of a predicament: The most effective drug to treat the cancer is also the most toxic.

Trastuzumab, sold under the brand name Herceptin, causes cardiac problems in about 15 percent of patients who take it. The chemotherapy drug causes their hearts to contract less vigorously, decreasing blood flow throughout the body. In the worst cases, it can lead to heart failure. The only recourse is to stop the medication — which, of course, means less effective treatment for the cancer.

But clinicians may soon be able to predict which patients will experience heart problems, and they may have a drug, already approved by the Food and Drug Administration, that can lessen the side effects.

The research is described in an article published in Circulation by senior author Joseph Wu, MD, PhD, professor of cardiovascular medicine and of radiology.

As Wu explains in our press release:

We could use this method to find out who’s going to develop chemo-related toxicity and who’s not. And now we have an idea about the cardioprotective medications we can give them.

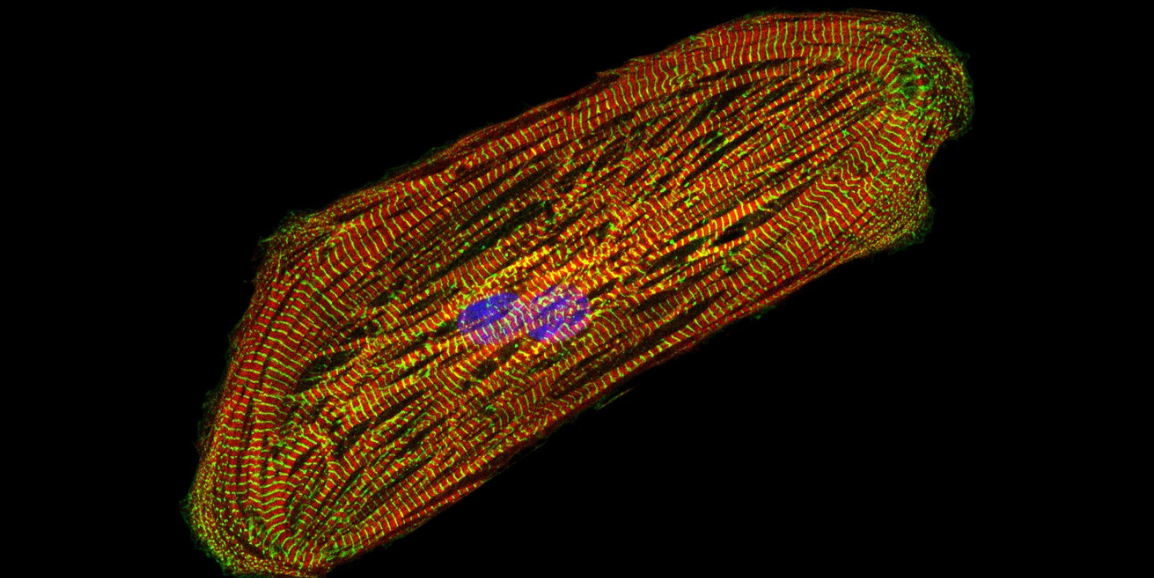

Wu and his fellow researchers conducted the research in a lab, using cardiomyocytes, or heart cells derived from blood. (That’s a cardiomyocyte in the photo.) The blood was drawn from breast cancer patients, some of whom had cardiac side effects from trastuzumab and some who didn’t.

When the researchers applied trastuzumab to the heart cells, they found that those from patients who suffered cardiac problems contracted less vigorously. Those from patients who experienced no side effects contracted normally.

Knowing that a class of medications, AMPK inhibitors, can boost cell energy, they fed them to the weakened heart cells. As the researchers expected, the heart cells beat more vigorously. One of the AMPK inhibitors they tested is metformin, a drug commonly used to treat Type 2 diabetes.

For their next steps, the researchers plan to look at previous HER2-positive breast cancer patients who also had diabetes. They want to see if patients who were on metformin experienced fewer cardiac side effects from trastuzumab than patients who weren’t taking metformin. If that pans out, they plan to run a trial in which they give metformin to patients taking trastuzumab.

According to Wu, research on these types of cells opens the door to “clinical trials in a dish,” in which drugs can be tested without exposing people to side effects — along with reducing costs and the time spent developing medications. As Wu said, “This will significantly cut the cost of drug development, providing better and more affordable drugs to the population.”

Image of a cardiomyocyte courtesy of the Wu lab